|

Главная Случайная страница Контакты | Мы поможем в написании вашей работы! | |

Ammeters and Voltmeters

|

|

The action of almost all the types of measuring instruments is such that an electric current as distinct from an electric potential, is primarily responsible for the ultimate mechanical force required to produce movements of the instrument pointer. This has an exceedingly important influence on the practical forms of ammeters and voltmeters. By this is meant, that all, except the electrostatic type of instrument, are fundamentally current-measuring devices. They are fundamentally ammeters. Consequently, most voltmeters are merely ammeters so designed as to measure small values of current directly proportional to the voltages to be measured. It is only natural, therefore, that voltmeters and ammeters should be classed together.

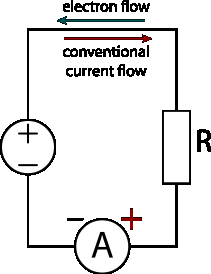

Ammeters, which are connected in series in the circuit carrying the current to be measured, are of low electrical resistance, this being essential in order that they cause only a small drop of voltage in the circuit being tested, and accordingly absorb a minimum power from it.

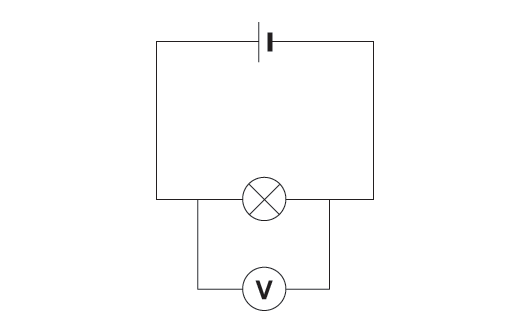

Voltmeters are connected across, that is, in parallel with, the circuit points where the voltage is to be measured, and are of high resistance, in this case sufficiently high so that the current flowing in the voltmeter, and the power absorbed from the circuit, are as small as possible.

The principle upon which both of these devices operate is essentially the same as that of the electric motor, differing from the motor, however, in the delicateness of their construction and the restrained motion of the rotating armature.

A coil of fine copper wire is so mounted between the two poles of a permanent magnet that its rotation is restrained by a hairspring. The farther the coil is turned from its equilibrium or zero position, the greater is the restoring force. To this coil is fastened a long pointer at the end of which is a fixed scale reading amperes if it is an ammeter or volts if it is a voltmeter. Upon increasing the current through the moving coil of an ammeter or voltmeter the resultant magnetic field between coil and magnet іs distorted more and more. The resulting increase in force therefore turns the coil through a greater and greater angle, reaching a point where it is just balanced by the restoring force of the hairspring.

Whenever an ammeter or voltmeter is connected to a circuit to measure electric current or potential difference, the ammeter must be connected in series and the voltmeter in parallel. As illustrated in Figure 24 the ammeter is so connected that all of the electric current passes through it. To prevent a change in the electric current when making such an insertion, all ammeters must have a low resistance.

Hence, most ammeters have a low resistance wire, called a shunt, connected across the armature coil.

A voltmeter, on the other hand, is connected across that part of the circuit for which a measurement of the potential difference is required. The potential difference between the ends of the resistance Rx being wanted, the voltmeter is connected as shown. Should the potential difference across R2 be desired, the voltmeter connections would be made at C and D, whereas if the potential difference maintained by the battery were desired, they would be made at A and D. In order that the connection of a voltmeter to a circuit does not change the electric current in the circuit, the voltmeter must have a high resistance іf the armature coil does not have a large resistance of its own, additional resistance is added in series. Very delicate ammeters are often used for measuring very small currents too. A meter whose scale is calibrated to read thousandths of an ampere is called a milliammeter, one whose scale is calibrated in millionths of an ampere being known as a microammeter or galvanometer.

Дата публикования: 2015-09-18; Прочитано: 642 | Нарушение авторского права страницы | Мы поможем в написании вашей работы!